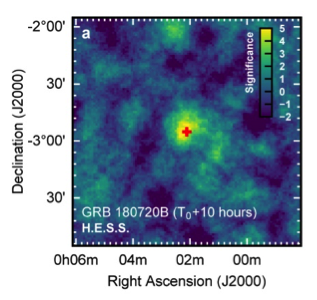

This is one of these rare moments: after decades of (quite often rather frustrating) searches we finally did it! What did we do? We detected very high-energy emission from a gamma-ray burst (GRB). These extremely energetic cosmic explosions typically lasting for only a few tens of seconds. They are the most luminous explosions in the universe. The burst is followed by a longer lasting afterglow mostly in the optical and X-ray spectral regions whose intensity decreases rapidly. The prompt high energy gamma-ray emission is mostly composed of photons several hundred-thousands to millions of times more energetic than visible light, that can only be observed by satellite-based instruments. Whilst these space-borne observatories have detected a few photons with even higher energies, the question if very-high-energy (VHE) gamma radiation (at least 100 billion times more energetic than visible light and only detectable with ground-based telescopes) is emitted, has remained unanswered until now.On 20 July 2018, the Fermi Gamma-Ray Burst Monitor and a few seconds later the Swift Burst Alert Telescope notified the world of a gamma-ray burst, GRB 180720B. Immediately after the alert, several observatories turned to look at this position in the sky. For H.E.S.S. (High Energy Stereoscopic System), this location became visible only 10 hours later. Nevertheless, the H.E.S.S. team decided to search for a very-high-energy afterglow of the burst. After having looked for a very-high-energy signature of these events for more than a decade, the efforts by the collaboration now bore fruit. A signature has now been detected with the large H.E.S.S. telescope that is especially suited for such observations. The data collected during two hours from 10 to 12 hours after the gamma-ray burst showed a new point-like gamma-ray source at the position of the burst. While the detection of GRBs at these very-high-energies had long been anticipated, the discovery many hours after the initial event, deep in the afterglow phase, came as a real surprise. The discovery of the first GRB to be detected at such very-high-photon energies is reported in a publication by the H.E.S.S. collaboration et al., in the journal 'Nature' on November 20, 2019. Who is "we"?

The results were obtained using the High Energy Stereoscopic System (H.E.S.S.) telescopes in Namibia. This system of four 13 m diameter telescopes surrounding the huge 28 m H.E.S.S. II telescope is the world's most sensitive very high-energy gamma ray detector. The H.E.S.S. telescopes image the faint, short flashes of bluish light emitted when energetic gamma rays interact with the Earth's atmosphere (so-called Cherenkov light), collecting the light with big mirrors and focusing it onto extremely fast reacting sensitive cameras. These Cherenkov images allow H.E.S.S. to reconstruct the properties of the interacting gamma-rays and ultimately detect their sources. The High Energy Stereoscopic System (H.E.S.S.) team consists of over 200 scientists from Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Namibia, South Africa, Ireland, Armenia, Poland, Australia, Austria, the Netherlands, Japan and Sweden, supported by their respective funding agencies and institutions. While I was not personally involved in the data analysis for this particular event, I am responsible for the searches for transient (i.e. rapidly fading) phenomena within the H.E.S.S. collaboration (technically speaking I am the convener of the "Transient" working group). Among the various topics covered in this group, searches for emission from GRBs have always been (and will obviously remain) the highest priority. Other searches include the quest for gamma-ray emission associated to Gravitational Waves, high-energy neutrinos, Fast Radio Bursts, Novae and Supernovae as well as flares from AGN, stars, magnetars, etc. What does this mean and what is next? The very-high-energy gamma radiation which has now been detected not only demonstrates the presence of extremely accelerated particles, but also shows that these particles still exist or are created a long time after the explosion. Most probably, the shock wave of the explosion acts here as the cosmic accelerator. Before this H.E.S.S. observation, it had been assumed that such bursts likely are observable only within the first seconds and minutes at these extreme energies. At the time of the H.E.S.S. measurements the X-ray afterglow had already decayed very considerably. Remarkably, the intensities and spectral shapes are similar in the X-ray and gamma-ray regions. There are several theoretical mechanisms for the generation of very-high-energy gamma light by particles accelerated to very high energies. The H.E.S.S results strongly constrain the possible emission mechanisms, but also present a new puzzle, as they request quite extreme parameters for the GRB as a cosmic accelerator. Together with the observations of very-high-energy gamma radiation following later GRBs with MAGIC (published in the same edition of Nature on Nov. 20, 2019) and again with H.E.S.S. (GRB190829A), this discovery provides deeper insights into the nature of gamma-ray bursts and opens the window for deeper observations and further studies. For more than a decade, Cherenkov telescopes such as H.E.S.S., MAGIC and VERITAS have searched for very-high-energy gamma radiation from GRBs and continuously improved their observation strategies. Now several GRBs have been detected at very high energies within a very short time, and we now know that these bursts are emitting at extreme energies for many hours. This opens entirely new perspectives for further observations with the current instruments and is even more promising for the successor instrument, the Cherenkov Telescope Array, which will enable us to study these stellar explosions in much more detail. A few highlights of the media coverage:

1 Comment

|

AuthorMyself ;-) Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed